AN

ALTERNATIVE APPROACH TO MULTINATIONAL INVESTMENTS AMONG INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES.

Background.

The geothermal potential of the

Kenya Rift Valley was recognized in the mid-1950s. In 1956, two wells were

drilled at Olkaria about 10 km west of Longonot. With promising results the

UNDP and the Kenya Power and Lighting Company carried out an extensive

exploration program in the Rift Valley in 1970. This survey identified Olkaria

as the best candidate for exploratory drilling.[1]

By 1976, six deep wells had been drilled and the first 15 MW generating unit

was commissioned at Olkaria in 1981.

|

Fumes

from the geothermal plants/ Jackson Shaa

|

Since

2009, infrastructure financing to Africa has seen unprecedented growth. Chinese

financing, official development financing (ODF), and private participation in

infrastructure (PPI) investments have been key sources in this rapid growth—as

have national African governments and their domestic resources. Kenya in particular

has seen such growth on the development of renewable energy in form of

geothermal development.

The

Government of Kenya has placed considerable importance on the Technical and

Economic Study for Development of Small Scale Grid Connected Renewable Energy

in Kenya. Since 2008, feed-in tariffs (FiTs) have been on offer to encourage

investment in renewable energy (RE) generation projects, but there has to date

been a rather limited response as measured by numbers of projects implemented

under the FiT mechanism. The Government seeks now, with the assistance of the

World Bank, to create a framework which will encourage greater RE investment,

thereby relieving the capacity constraint and allowing more Kenyans to connect

to the grid, but at the same time avoiding high tariff increases being imposed

on existing electricity consumers.

While

this has been the case, most of the projects that have been implemented have

raised major concerns of lack of proper protocols for community involvement,

irregular and skewed compensation for communities and more so forceful

evictions of local communities that live within project sites. These anomalies

were further given credence by an initial investigative report by the World

Bank Inspection Panel which visited the general area to validate complains that

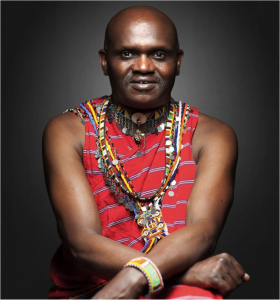

were lodged by the Maasai community[3]. Among the key issues that

the initial report identified were; land titling, identification of Project

Affected People (PAPs), livelihood restoration, benefit sharing, redress and

implementation support, and the issue about indigenous people.

Inadequate

Environmental and Social Impact Assessments

Furthermore, geothermal resources in Olkaria have been exploited

with no regard for the health or environment of the local communities. Despite

being touted as a green energy, KenGen’s Environmental and Social Impact

Assessment shows that geothermal power plants release certain pollutants into

the environment including noise pollution, hydrogen sulphide gas, and trace

metals like boron, arsenic, and mercury. Toxic wastes from the power station in

Naivasha have been emitted into the air and disposed in local waterways in

violation of applicable international environmental standards (Marine Power,

2012).

It is an expected norm that before any

project is undertaken, an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) has

to be done. An ESIA is a process or set of activities designed to contribute to

pertinent environmental and social information in a project decision making

process. During an ESIA process, attempts are made to identify, predict, and

assess the likely consequences of the proposed project or program. It is

therefore a planning tool whose objective is to identify, predict and asses any

impacts that the proposed project may have in order to inform policy.

Apparently, the ESIA report that was

used by KenGen to seek funding lacks empirical data and insensitive to the real

needs and interests of the community to support the project and has a myriad of

gaping holes that any professional who is averse with that area will see on a

first glance. First, the report about the Maasai people shows a high level of

ignorance and disregard to the Maasai culture and their livelihood. The

following areas are of great concern both to the Maasai, wildlife, and the

general environment:

Disregarding

the Maasai people and their culture

The ESIA report negated the relevance

of indigenous peoples’ ways of lives and their livelihood and did not take into

consideration the Maasai belief and value systems. According to the report the

following areas raise a lot of concern on the people’s culture and belief:

a) under Part 1.3.3 of the ESIA,

paragraph (c) on Social change states that “with anticipation of coming of new people from varied cultures,

cultural exchange will lead to adoption of new ways of life, system of beliefs

and shedding off of traditional way of living that have stagnated development

in the local area[4]”.

This paragraph is highly discriminatory and stereotyped and to extend

prejudicial to the Maasai. By stating that the Maasai adopt new life styles is

demeaning and a proposition that other cultures are superior to the Maasai

culture. It is an indication of a clear bias by the consultant and to a greater

degree the ignorance of the authors of the Maasai way of life hence lacks

objectivity;

b) under 7.3.2: positive impacts during

construction; the report says that during construction, the local community

particularly women will get an opportunity to start small income generating

activities e.g. sale of food, this will diversify income streams and improve

socio-economic status. The reports negates the basic principle that Maasai that

live in the general area are pastoralists who also practice small scale

agriculture and transhumance. The report lacks in-depth knowledge of how

indigenous livelihood diversification has contributed to the sustenance of the

people over long periods of time. The

report ignored the fact that beadwork, crafts and the Maasai culture in itself

provided alternative incomes other than pastoralism’s to the community, and that

over time they had developed a secure source of income closer to the museum

where young men work as scouts and guides to earn income. There is no mention of Ilkarian village and

museum and how the linkages that the local Maasai had developed over time with

partners in Europe was hence not considered as an alternative income source for

the Maasai; and;

c) It is appalling how the report ignored the Maasai cultural,

spiritual, and life patterns. There is a very rich history of the Maasai dating

back 1800 for such sites like Enkaibartani, Olare: (orbene

lolchani – “bag of medicine”), Enkapune orpeles, Enchoro Oloontualan,

Enchoro Olormampuli, and graves.

By ignoring the grazing patterns the Maasai from Suswa who rely on the gorge as

a dry weather grazing area, and that most of the Maasai who live in Olkaria and

Narasha have extended families far and beyond the project area and there is

interdependence on the way of life is another great weakness of the report.

Lack of strategies to address people’s livelihoods

|

Livestock

grazing with geothermal plants on the background. Photo courtesy of Jason Patinkin

|

Disregard of environmental hazards

Lack of

knowledge of biodiversity species in the project sites

According

Nature Kenya[5]

experts in biodiversity clearly outlined the discrepancies of the ESIA report

which included wrong names for species that are found in the habitat. The

letter also gave detailed facts that

almost all of the species are endangered and that any further exploitation of

geothermal in the project site will lead to extinction of such species.

Environmental destruction and other hazards

KenGen has dug several disposal pits close to

the schools and the villages which not only pause a threat in the future but

have already claimed the life of one child and several livestock which fell to

the pits. The clearing of vast areas and piling of soils in areas that were

mainly used for pasture have not only reduced grazing areas for the local

communities buy have contributed to massive erosion that have created deep

gullies around the villages which are equally a threat to both human and

livestock. On the face of it, the clearing of the vegetation on the already

delicate fragile land topography has facilitated enormous erosion that will

take very many years to rehabilitate and as per the report there seems to be no

such mechanisms provided.

Health related impacts

According

to the report, there

are high chances that new infection rates of HIV/AIDS and STIs will increase

due to the money available to traders, workers and business people coming into

the area. There is factual evidence from

the community that unaccompanied men have brought STIs into the villages,

breaking up families and causing divorces. Worse still of workers impregnating

school children have been reported and the company protects its workers by

compromising the gatekeepers through bribery to stop legal action against

perpetrators of such vices. The deliberate spillage of the brine and other

waste materials without due diligence has continued to pollute the very few

water sources that are available.

Inappropriate

involuntary resettlement procedures and forceful evictions

|

Temporary

structures after displacements/ Stephen Parkire

|

The local

community have variously faced forced evictions accompanied by mass destruction

of property due to contestation of land ownership by the Maasai and another

group which claims to legally own the land which is historically the home for

thousands of Maasai family. Case in

|

Community

response to forceful evictions

|

Further to the forced evictions, the involuntary relocation

of the Project Affected People (PAPs) was not implemented in accordance to RAP.

There were also very clear discrepancies on land titling, identification of

PAPs, restoration of livelihoods and the absence of a transparent, democratic

grievance redress system. The grievance redress system which the government has

used is extremely intimidative and manipulation in that courts are now being

used to dismiss Maasai cases in order to allow for forced evictions[9].

Some members of the community are currently living under threats of retaliation

for raising complaints against the processes.

Recommendations

These recommendations are mainly

directed to the Government of Kenya which include the counties where the

communities reside, KenGen, the World Bank, European Investment Bank,

International Finance Corporation and the community.

General

recommendations

1.

Despite the fact that the World Bank and the European

Investment bank have carried out an investigation whose report is yet to be

made, there is an urgent need to institute a study on the processes and impacts

of the existing projects on the general wellbeing of the affected communities.

This will help in informing policy and future decision making.

2.

There is an urgent need to initiate a stakeholder mediation

process to identify key areas that need to be addressed, this will facilitate

trust building. Currently there is an overwhelming lack of trust in the companies

involved, lack of trust in government to resolve issues and monitor

resettlement impacts, lack of trust within the community leadership structures

which was brought up by the companies divide and rule approach, and conflicts

between the community and gate keepers that the companies have used as

community mouth pieces.

3.

A review and where possible a new Environmental and

Social Impact Assessment which is indigenous people led be done with experts

from various relevant fields involved.

Recommendations

for the Kenya government

· There is

need to establish strategies that work with the County and national governments

to establish and support community-based livelihood restoration activities in

in the affected area including sustainable income generation. Consideration

must be given to income-generating strategies that are suitable for women and

youth.

· Need for

the adherence and strengthening of the legal frameworks consistent with the

resolution of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to “ensure

participation, including the free, prior and informed consent of communities in

decision-making on natural resource governance[10].

· The

government need to develop a National Action Plan to implement the United

Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights with specific reference

to identifying, mitigating and preventing the potential human rights impacts of

resettlement.

· The

government should enforce the requirement that all companies seeking approval

for extractive projects ensure that essential resettlement infrastructure is

established prior to physical relocation.

Recommendations

to the WB, IFC, EIB, KenGen and IPP

· Creation of

an emergency fund to finance an urgent mediation process between KenGen, the

community and other stakeholders. Activities to be funded will include community

organization, knowledge and skills transfer, research on alternative

livelihoods, strengthening of indigenous leadership and governance structures;

and institutions, facilitate processes for an enabling environment for benefit

sharing as opposed to the current approach where local communities are given

one time compensation. This process should be led by indigenous peoples’

experts. This fund should also be used to support local communities to hire

experts to undertake monitoring of all processes.

· Need for support to

local civil society groups to assist communities to have access to, and understand,

project information including details about project owners and developers,

operators, subcontractors and relevant financial institutions.

· Finance an an in-depth

study to be carried out on alternative livelihood for the potential PAPs and

RAPs, and provide start- up capital for affected communities.

· World Bank

country offices should enhance their relationships with indigenous peoples’ through

the support of initiatives that increase funding for capacity building,

livelihood support and institutional strengthening.

Conclusion

Since community

capacity is the interaction of human, organizational and social capital

existing within a given community that can be leveraged to solve collective

problems and improve or maintain the well-being of a given community, and may

operate through informal social processes and organized efforts by individuals,

organizations, and the networks of associations among them and between them and

the broader systems of which the community is part, relationships within a community

not only serve as the basis for the community to solve its own problems, they

also are used to obtain resources and influence public policies and the actions

of the private sector that affect the quality of life in the community. It is

therefore of paramount importance that deliberate, targeted community capacity

building becomes the forerunner of any investments that are undertaken within

indigenous peoples lands and territories.

Proposed remedies for the

current conflict in Narasha, Kedong, and Suswa where the community is up in

arms will be:

a.

a mediation process between the community, the investors,

the Independent Power Producers and the government, and the process should be

indigenous people expert led to allow for trust building;

b.

since costs have already been incurred, and the rights of

the people have been infringed, a study needs to be financed by the investors

to identify potential opportunities to remedy the situation which will include

an all –inclusive ESIA;

c.

for communities that are yet to be relocated (displaced),

there is need for honest and inclusive dialogue to be facilitated by an

indigenous professional experts (as opposed to the past where KenGen and other

companies were using gate keepers who were compromised) to rubber stamp

decisions; and

d.

an in-depth study to be carried out on alternative

livelihood for the potential PAPs.

Given that the government has

already given out concessions for further drilling which is expected to begin

any time depending on availability of funding, there is an opportunity to

forestall the conflicts like what have been experienced with the current project.

Such opportunities will include: The revision of the previous ESIA to reflect

the reality and to include the indigenous peoples’ perspectives, community

councietization, capacity enhancement and establishment of community

institutions to partner with prospecting IPPs for purposes of benefit sharing

and co-ownership of the investments as opposed to the current situation where

the communities only receive one time compensation, deliberate move to

facilitate indigenous people to establish business ventures that will partner

with potential venture investors, consultations on the locations where PAPs

will be resettled, and the types settlements as well as social amenities they

will require.

More important, investments being carried out

on indigenous peoples’ lands and territories should recognize the indigenous

peoples’ right to self-determination,

“indigenous peoples have the right to determine priorities and strategies for

the development or use of their lands and territories”[11].

It is of importance here to stress the fact that the Kenya government not only

support and facilitate processes that build the capacity of local communities

to be able to initiate entrepreneurial project that harness their local natural

resources, but it also has the obligation not only to respect human rights by

refraining from conduct that would violate such rights, but also to

affirmatively protect, promote and fulfil human rights[12].

Emphasis is hereby made to ensure that the Kenya government support should

include providing assistance for acquiring any necessary licenses or permits.

Also, in granting any licenses or permits, the government should give

preference to indigenous peoples’ initiatives for resource extraction within

their territories over any initiatives by third party business interests to

pursue resource extraction within those same lands.

Finally for the indigenous peoples’ whose lands and territories have

either existing development projects or have been earmarked for investments,

the government has to ensure that there is security of tenure through land

rights and land management mechanisms, put in place mechanisms that will ensure

realistic, feasible and sustainable economic development, strengthen governance

and institutional strengthening of local institutions, and develop policies and

systems that are supportive of indigenous peoples’ wellbeing.

Koissaba,

B. R. Ole. Ph.D. (ABD)

Social Development Specialist

Clemson

University, SC,

[1] Kenneth B. A. & Greg U. (2011). Geothermal

resource assessment for Mt Longonot, central rift valley, Kenya. Proceedings, Kenya Geothermal Conference.

[2] Silas M. Simiyu, (2008). Status of geothermal

exploration in Kenya and future plans for its development

[4]

See Final Olkaria V Study

[5] See letter to KenGen from Nature Kenya

[6] See Oxfam: Mining, resettlement and lost livelihoods

[9] See Koissaba, B.R.Ole (2014). Kenyan Government

Manipulates Courts to Dispossess the Maasai of Their Lands.http://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/kenyan-government-manipulates-courts-dispossess-maasai-their-lands

[11] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, art. 32, para. 1.

[12] This obligation is grounded for all Member States in

the Charter of the United Nations, articles 1, 2 and 56, among others, and is a

general principle of international law; it applies in respect of those human

rights found in treaties to which States subscribe and in other sources of

international law.